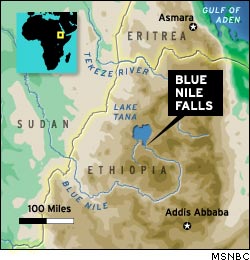

BLUE NILE FALLS, Ethiopia - The Blue Nile

brought me to Africa in 1973. To locate its source -- Quaerere caput

Nili -- had been the hope of many great captains and geographers of

the classical age: Herodotus, Cyrus and Cambyses of Persia, Alexander

the Great, Julius Caesar, Nero. The first Briton to make his way to the

source, perhaps in search of the Ark of Covenant, was the Scot James

Bruce. I had been enthralled by the writings of Bruce and of Alan

Moorehead, whose book "The Blue Nile" swept me into a world

beyond the pages of "National Geographic". I started a

correspondence with Moorehead, who lived in Switzerland in the late

1960s, and before he died he sent me a note urging me to travel to

Ethiopia to see firsthand the stories he had told.

So, in 1973 I made my way to the Ethiopian highlands and the Blue Nile,

and found myself standing on a mist-swept palisade transfixed by the

150-foot-high Tissisat Falls (smoke of fire), more popularly known as

the Blue Nile Falls. They were the most glorious display of falling

water I had ever seen.

James Bruce, in his search for the source of

the Nile, came upon the falls in 1770 and described it thusly: �The

river ... fell in one sheet of water, without any interval, above half

an English mile in breadth, with a force and a noise that was truly

terrible, and which stunned and made me, for a time, perfectly dizzy. A

thick fume, or haze, covered the fall all around, and hung over the

course of the stream both above and below, marking its track, though the

water was not seen. ... It was a most magnificent sight, that ages,

added to the greatest length of human life, would not deface or

eradicate from my memory.�

|

|

Deirdre Allen Timmons

Ethiopia's water authority briefly restored the flow of the

Blue Nile Falls so that an IMAX film crew, its post seen at

forefront, could film the area.

|

When I first stood before the immense manitou of the Blue Nile Falls,

watching the water spout and bloom like gargantuan brown mushrooms and

the mist shape and move like a timelapse sequence of clouds, I was

struck by how accurate Bruce had been and how little the sight had

changed in more than 200 years. The other great waterfalls of the world

-- Niagara, Iguazu, Victoria --are all now pocked with hotels and

tourist boutiques and scenic flights. At the Blue Nile Falls, however,

there was nothing save the raw, deep voice of nature and an architecture

supported by the brilliant beams of rainbows. I had no reason to

consider they might ever change.

Return for IMAX film

My return to The Blue Nile this year was pulled into motion

with a call from MacGillivray Freeman Films, the IMAX film producer of

"To Fly," "Everest" and others. The company was

co-producing a new IMAX entitled, "Mystery of the Nile". The

concept of the film was tracing the waters that slake and fertilize

Egypt from the headwaters of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, through the

Sudan, across Egypt and into the Mediterranean at Alexandria. While the

White Nile is the longer of the two streams that join in Khartoum to

create the Nile proper, it is the Blue Nile that contributes about 85

percent of the water that powers Egypt, and most of the precious silt

that nourishes its banks. If the Blue Nile dried up, or was dammed or

diverted in a significant way, Egypt would die.

|

The IMAX film planned on featuring several key scenes at the Blue Nile

Falls, the grandest cataract in the whole of the Nile system, and the

producers asked if I would codirect. So, in October, during a scout for

the film, I chartered a Cessna and winged up the Blue Nile towards the

falls. As we wound up the brown, serpentine ribbon, I was anxious to

figure out how to film the falls in the IMAX format in a way that would

do them justice.

But anxiety turned to anticipation as we

approached. Early October was the best time to see the falls, just after

the rains, and I knew I was in for an aerial treat.

But as I gazed downwards something was wrong

� the falls were but a shadow of how I remembered them � instead of

a blazing curtain of water half a mile wide, only about a third of the

basaltic lip hosted water. The rest, it seemed, was rolling down a giant

canal to the west of the river, into a massive concrete spillway. What

had happened to the great falls? The plane circled with my nose pressed

against the window, stunned at the sight.

I spent the next two days meeting with local

officials securing permissions for the shoot. When I finally made my way

down to Tissisat it was Sunday, and the falls were as I remembered, a

plunging diadem of water slinging mist into my face.

The scenes envisioned for the film included

lowering rafts over the wall of the falls, rappelling down its side, and

sending over a �ghost boat,� an unmanned, unrigged raft, as the

British Army had done in 1968 during an attempted descent of the river.

The falls were full enough to make this all happen, but I was curious as

to why a few days earlier the falls seemed to be a fraction of this

Sunday�s volume.

Flow diverted by hydropower project

Yohannes Assefa, our local outfitter for the project, did

some digging around and said that a new $63 million, 450 megawatt power

generating station called Tis Abay II was just gearing up, diverting

water on weekdays, but not yet on Sundays and holidays when there was

less demand for the power. This news was disturbing.

More than 90 percent of energy consumed in Ethiopia is derived from

biomass fuels and is almost entirely used for cooking, and the use of

these fuels has resulted in massive deforestation and soil erosion. Only 4

percent of the population has access to electricity. Yet Ethiopia, which

sits atop a mile and half high plateau, has huge rivers and canyons

hurtling off all sides, offering vast hydropower potential. But the only

reason to compromise the Blue Nile Falls, one of the great natural

wonders of the world, would be to tap into power cheaper and faster. An

hour flight in any direction reveals scores of deep gorge alternatives.

I didn�t quite believe it, and when back in

the United States Googled the Web and searched to see if there were

any further explanations. But I could find nothing ... just a slew of

travel companies offering tours to see the singularly splendid falls in

the coming weeks, the traditional high season.

Fearing the worst, though, I scheduled the

falls scenes for Sunday for when we returned a month later. But when we

arrived mid-November, a week prior to the shoot to make final

arrangements, I was shocked beyond shock. It was the Sunday before the

scheduled shoot when I walked up the familiar path to the palisade

overlook of the falls and saw almost nothing there. A thin ribbon of

water scraped down the cheek of the dark cliff that once was a

breathtaking spectacle, and an icon for the Ethiopia.

The country�s paper currency, the one birr

note, proudly showcases the falls in spate; posters of the falls plaster

offices and restaurants around the country. Yet the falls were gone, 90

percent diverted into this new power scheme built by Chinese and

Serbian contractors. The river was redeposited a few hundred yards

downstream after pouring through penstocks and turbines, but it had left

the great falls bald and sallow.

Impact on locals, tourists

This seemed a crime against nature, against aesthetic sensibilities,

even against local economies. The village women and children who sold

calabashes, weavings, sodas, trinkets and walking sticks to tourists

complained to me how their livelihood was suffering. Tana fishermen

carped that the lake was being drained to keep diversion flows steady,

and lower lake levels were exposing fish hatcheries, reducing the fish

population.

|

|

Deirdre Allen Timmons

Surprised locals watch the restored, albeit temporarily, flow

from the Blue Nile Falls.

|

Back at the hotel I kept running into angry Western tourists who had

spent hundreds of dollars and sometimes hours of flying to witness the

Blue Nile Falls at their best and now felt snookered. Tourism, which had

dropped to a trickle under the radical socialist regime of Mengistu

Haile Mariam in the 80s, had been coming back under the new

administration of Meles Zenawi, and the Blue Nile Falls was a top draw.

But no more. Before constructing the diversion dam, the Ethiopian

government hired consulting firms from France and Britain for the

feasibility study. The study concluded that, unlike other hydropower

projects with big dams, Tis Abay II would have �negligible

impact on the environment, and that it would be economically very

attractive for investment.� Somehow, though, the project sailed to

completion without the cognizance of any international environmental

watchdog group, or any journalists. This was the first season the

diversion project had been put into full effect, and the first time

tourists were discovering that what they had come to see had vanished,

gone with manmade legerdemain.

And it put the film in a dilemma. The conceit

was more about the historical aspects of the water that flowed to and

fed Egypt, though it imagined the spectacular falls and scenes of modern

adventurers recreating some of what the British army had done. The film

could change its concept and take an environmental stance, exposing the

stealing of the falls by short-sighted, power-hungry bureaucrats. But

the falls were just plain ugly in their current state, not an IMAX

moment, which is a scene of preternatural beauty shown in

high-definition large format. So, we devised another solution. We called

the vice minister of water resources and explained our film and its

purpose. And after much negotiating he agreed to close the dam for us

for four hours to film the falls in full.

We spent the week filming the rapids above the

falls as planed. At one point, though, our team was arrested and the

boats confiscated as we floated down a 400 yard section of the river

about 20 miles above the falls where the Blue Nile has yet another

recent diversion, a low height weir that allows regulation of the water

flow from Lake Tana, its source. A few hours after appealing to

the local police commissioner, everyone and everything was released, but

again we had stumbled into a little-known scheme that was altering the

balance of nature.

Falls turned back on, briefly

At last, on the given day, we gathered at the falls, and watched it rise

to its previous levels. It was as breathtaking as it had ever been. We

filmed our scenes of rappelling, roping boats over, and pitching an

empty raft down the plunge, all fantastic, but somehow tinged with

melancholy, knowing it was not quite real. Some lucky tourists wandered

over to the viewpoints and were delighted with the falls, not knowing

what they were beholding was a scene not available in a few hours time.

A few days later we wrapped the Ethiopian

portion of the film, and I boarded the Ethiopian Airlines flight back to

Addis Ababa, the capital, where I would connect with an international

flight home. As we took off, the pilot circled over the falls, as he had

done for years to show off his country�s greatest natural asset to the

tourists on board. But as he dipped his wings, and I looked straight

down to the where the Nile makes its greatest plunge, there was nothing

there. Just a cold, gloomy empty cliff.

The second chapter of the book of Genesis

refers to the rivers that flow through the Garden of Eden: �And the

name of the second river is Ghion; the same is it that compasseth the

whole land of Ethiopia.� The Blue Nile, sweeping out from Lake Tana in

a wide loop, does indeed encompass the ancient land of Ethiopia. Though

today the fountain of this paradise is turned off, and the garden of

grasses, reeds, leaves, and lush trees and plants once showered with a

perpetual spray from the falls, are now brown and dry, edenic no more.

Richard Bangs co-directed "Mystery of

the Nile," scheduled for release in the fall of 2005, and was

recently editor-at-large for Expedia.com. He also is co-founder of

Mountain Travel-Sobek, and author of 13 books. His latest is

�Adventure Without End.�